The boom in artificial intelligence and machine learning has led to concerns about the reinforcement of social bias by algorithms. Books like Cathy O’Neil’s Weapons of Math Destruction and Virginia Eubanks’ Automating Inequality examine how machine algorithms have furthered existing biases in the culture. There is a longer history to this problem than you might think, one that goes back to the prehistory of electronic computing itself.

As algorithms are applied to critical social decisions, like who gets a job or who can buy a home, the social impact of very complex software comes to matter more and more. The question of what this technology is and how we use it is one we must comes to grips with at both a social and a political level. And, I would argue, we need to understand it in a historical context as well.

The question of the impact of social and political questions on computing is not new. Modern electronic computing was born in the aftermath of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War. Famously, the first test program for the 1945 ENIAC was a computation for the hydrogen bomb. But the political and social roots of computational bias go deeper than this.

One of the main sources of modern electronic computing technology is the punched card tabulator, invented by Herman Hollerith and used in the tabulation of the 1890 census. The technology became the basis for Hollerith’s company, the corporate ancestor of IBM.

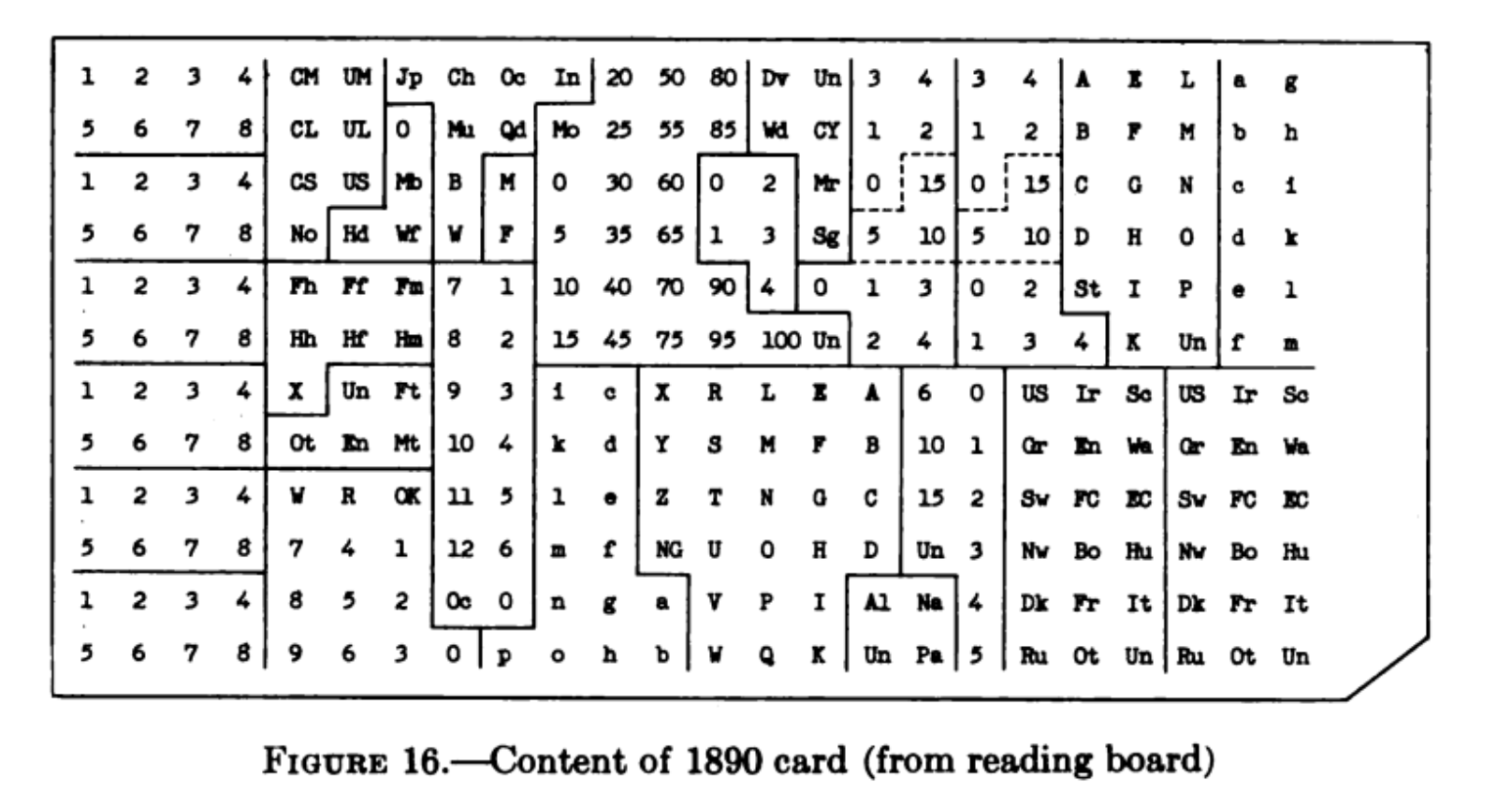

In Hollerith’s system, data for an individual was captured in a punched card. A hole punched at a particular position on the card meant that the individual had a particular characteristic. For example, on the card below, you can see a field with the values “M” and “F”. A hole punched at M indicated a male, one at F a female, and if both were punched the machine threw an error. The field captures a social bias — an exclusive binary representation of gender identity.

Less obvious, perhaps, is the meaning of the field above and to the left of the gender field. This field contains the values for race — “Jp”, “Ch”, “Oc”, “In”, “Mu”, “Qd”, “B” and “W”. “Jp” stands for Japanese, “W” for white, and “In” for Indian (Native American). Four of the values — “B” for black, “Mu” for mulatto, “Qd” for quadroon and “Oc” for octoroon — stand for degrees of blackness, fractions of African heritage.

The census had in essence been asking about race ever since its beginnings. It was originally intended to determine the number of representatives each state would send to the House of Representatives, and because of the Constitution’s infamous three-fifths clause it was necessary to know whether an individual was free or a slave in order to make that calculation. But over the course of the century and especially after the Civil War there was a growing interest in the racial characteristics of white and black Americans. In particular, a group of race scientists espousing a theory called polygenism — “belief in multiple origin” — argued that whites and black represented were so different that their offspring would be weakened, like mules (the offspring of horses and donkeys). The question about degrees of blackness in the 1890 census came from those debates and the data collected was intended to contribute to them.

The history of polygenism, late nineteenth-century race science and the rise of statistics is much too complicated to describe here. It is only one illustration of a fact that any student of the American political system already knows — the census is a highly politicized process. We sometimes forget how crucial the political process was in the origins of punched card technology, and therefore, in the history computing. Computing, seen from this angle, is inherently political, because it arises from the give and take that characterizes the political process.

Hopefully this very brief discussion will show that the issues we are grappling with now around computing, society and bias are not new. I believe they are wired into the technology itself, because technology is created in a socio-cultural context. It may be possible to unwire them, but to do that first we have to understand how deep the problem goes.